March 2008

Volume 11, Number 4

| Contents | | | TESL-EJ Top |

|

March 2008

|

||

|

gmail.com>

gmail.com>

This article looks at what constitutes an open educational resource and considers the issues and benefits to an educational institution that is moving to participate in open educational resource development and to adopt more open educational practices. It describes the initial steps in these directions being made by the Educational Development Centre at Otago Polytechnic, a tertiary educational and vocational training institution in Southern New Zealand. (The original, unedited version of this article is also available online at Blackall (2007b)).

In a recent First Monday paper, titled "The Genesis and Emergence of Education 3.0 in Higher Education and its Potential for Africa," Keats and Schmidt (2007) describe an educational system that benefits from international and cross-cultural relationships and the adoption of open educational resources (OERs) and practices to improve operational effectiveness and the quality of teaching and learning services. At the same time, "Networks, Connections and Community: Learning with Social Software," a report from the Australian Flexible Learning Framework (Commonwealth of Australia, 2007), looks at current and future uses of socially networked software in educational settings, specifically pointing out the need for OERs, diverse professional networks, and embedded new practices to realise the potential for a new form of socially constructed learning.

Such papers and reports describe a steadily increasing trend in the education sector. This trend is by and large a response to the significant successes of social-justice driven innovations, such as the Wikimedia Foundation [http://wikimediafoundation.org] projects; Ourmedia [http://ourmedia.com], and the Internet Archive [http://archive.org] initiatives; the vastly popular market-driven self-publishing platforms, such as blogs, audio, video and photo sharing services (otherwise known as social media or Web 2.0); and the notable increase in Open Courseware and OER initiatives coming out of educational institutions.The Internet inherently lends itself to openness, and to a large degree has brought about the need for more open practices in sectors that rely on information and communications technologies. However, copyright laws, incomplete or incompatible intellectual property policies, cultural sensitivities, commercial operations, and general ignorance are all issues that need to be overcome if educational institutions and the OER platforms are to realise the mutual benefits of open educational practices and resources.

This article will focus on specific issues relevent to a small New Zealand vocational training and education institution, Otago Polytechnic, and its initial attempts to develop OERs and practices that utilise socially networked information and communication techniques. Otago Polytechnic graduates an average of 1,987 students per year. In 2006 it established an Educational Development Centre to assist the institute in developing flexible learning programmes and staff training activities with an eye towards an Education 3.0 future.

In 2002, the Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT) began a project called MIT OpenCourseWare, with the aim of gradually publishing all educational resources and curricula with copyrights:

[We] invite educators around the world to draw upon the materials for their own curricula, and we encourage all learners to use the materials for self-study. . . We hope the idea of openly sharing course materials will propagate throughout many institutions and create a global web of knowledge that will enhance the quality of learning and, therefore, the quality of life worldwide. (Vest, 2002, n.p.)

And thus began the wider use of the term Open Courseware. MIT's hope did eventuate with many other educational organisations announcing Open Courseware projects. In July 2005, David Wiley developed the OpenCourseware Finder [http://ocwfinder.com], a search engine focused specifically on finding open courseware from a number of educational institutions (see Wiley, 2005), and later that year the Open Courseware Consortium [http://ocwconsortium.org], also based in Massachusetts, was established. It currently lists over 100 educational organisations from around the world publishing open courseware.

Open Educational Resources (OER), according to the Wikipedia article, is a term first adopted at UNESCO's 2002 Forum on the Impact of Open Courseware for Higher Education in Developing Countries. The Wikipedia entry defines open educational resources as "educational materials and resources offered freely and openly for anyone to use and under some licenses to re-mix, improve and redistribute."

The hugely successful Wikipedia [http://www.wikipedia.org], currently ranked in the world's Top Sites by Alexa, and easily the world's largest OER, by the time of MIT's and UNESCO's announcements had been operating for over twelve months and had grown in that time from an initial 8,000 articles in January 2001 to 88,291 articles in the English version by October 2002. Today it has 251 language editions, with the English version alone containing 1,778,031 articles. In 2003, the Wikimedia Foundation was announced as an umbrella organisation that would encompass Wikipedia and the other open and collaborative authoring initiatives: Wikiquote [http://wikiquote.org], Wikibooks [http://wikibooks.org] editable textbooks (including Wikijunior [http://en.wikibooks.org/wiki/Wikijunior/] for children), Wikisource ([http://wikisource.org] a free library, including poetry, news, etc.), Wikimedia Commons [http://commons.wikimedia.org] (media files), Wikispecies ([http://species.wikimedia.org] an encyclopedia of life forms), Wikinews ([http://wikinews.org] news you can write), Wikiversity ([http://wikiversity.org] free learning materials, content, and resources), and Meta-wiki ([http://www.meta-wiki.com] free Web services, for example, domain names, hosting, design tools, etc.) All these projects are linkable from the Wikimedia Foundation and from each other, and are available in many world languages. If these other wiki projects grow at anything like the rate at which Wikipedia is growing, the Wikimedia Foundation will easily house the world's largest open educational resources.

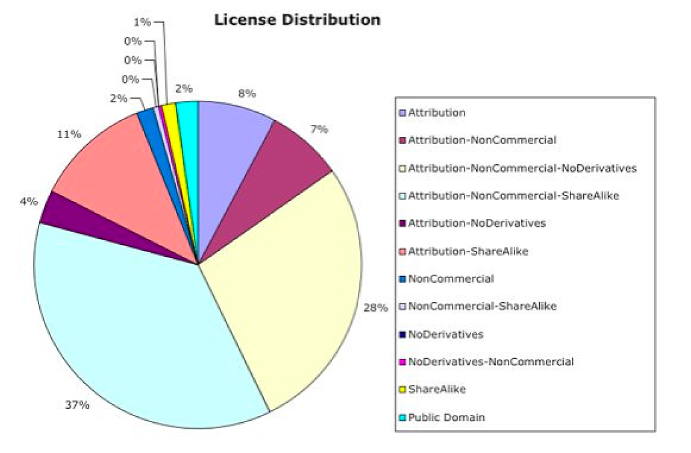

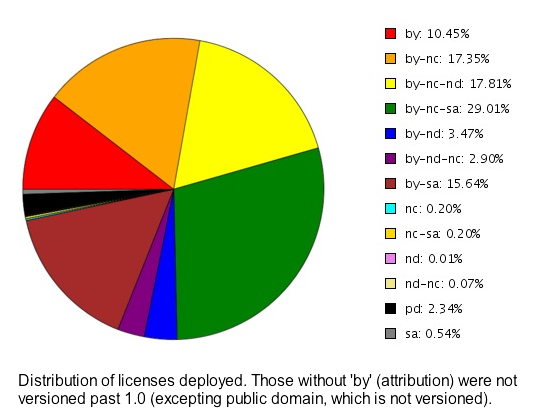

With the proliferation of a range of OERs, from courseware to reference materials and other media, the most important aspect of all these resources is their openness, first and foremost, their opennesss in terms of visibility, access, and initial use. However, the use of the word open can be problematic, as the word itself does not necessitate consideration of the freedoms to remix, make improvements on, or redistribute the resources. Even though the intentions stated by many of the leading projects appear clear, all of it is ultimately controlled by the copyright license that is assigned to a resource, and often that choice can result in a resource not being nearly as open as one might first have thought. In the case of MIT's Open Courseware, the copyright license on those resources is a Creative Commons [http://creativecommons.org] license, with Share Alike and Non-Commercial restrictions. These restrictions, in particular the Non-Commercial restriction, have been criticised for the limits they place on others' ability to remix, make improvements on, and redistribute the resources (see Müller, 2005). How does a user who is affected by these restrictions reconcile them with the grand statements made by the various project leaders? How can other institutions that are partly commercial and partly restricted in their own uses of resources utilise or participate in open educational resource projects that come with such restrictions? (See Figure 1 for licensing statistics in 2005, and Figure 2 for statistics in 2006.)

Figure 1. Distribution of licenses in 2005 after Yahoo Indexed Creative Commons licensed works (Paharia, 2005).

Figure 2. Distribution of licenses in 2006 (Creative Commons, 2007).

In an attempt to clarify the copyright confusion surrounding OERs, and to assist open educational projects in making better choices in copyright licenses, the Definition of Free Cultural Works (2007) may be useful:

This document [the wiki] defines "Free Cultural Works" as works or expressions which can be freely studied, applied, copied and/or modified, by anyone, for any purpose. It also describes certain permissible restrictions that respect or protect these essential freedoms. The definition distinguishes between free works, and free licenses which can be used to legally protect the status of a free work. The definition itself is not a license; it is a tool to determine whether a work or license should be considered "free" (n.p.; see also the wiki revision history, Müller & Hill, 2007).

However, licenses such as Share Alike (SA) and GNU Free Documentation License (FDL) are included in this definition and they both contain restrictions that do not allow someone to freely modify and redistribute a modified work without agreeing to utilise the same or a compatible license on the derivative. It is possible to use multiple licenses on a work that is made up of combined documents, but impractical or impossible in the case of modifications and derivatives. The Definition of Free Cultural Works tends to be contradictory and possibly misleading in its acceptance of SA and FDL restrictions. For example, terminology such as, "free licenses which can be used to legally protect the status of a free work," is misleading because mechanisms within the SA or FDL (commonly referred to as copyleft) do not protect the freedoms of the original work as much as they ensure and promote the re-usability of a derivative work, and so the terminology might be more accurate if it were, "licenses that restrict reuse so as to ensure the same or compatible licenses are assigned to derivative works," where the notion of "freedom" is more squarely aimed at the derivative work that is yet to be licensed, and not at the original work that is already free by virtue of its Attribution license without the SA provision.

Considering the purpose of an OER, the license should be one in which attribution to original authors is all that is required in its reuse. This practice should be familiar and comfortable to educational institutions, and it is a license that maintains maximum re-usability and flexibility of an original resource. It makes little sense to apply any further restrictions, such as Non-Commercial, SA, or even FDL to an OER that is intended to be available for remix, modification and redistribution in as wide an educational context as possible. Furthermore, for the purposes of this article and to generate interest and discussion, a superficial analysis of statistics in the use of Creative Commons licenses, particularly comparing the growth in use of the Attribution license compared to the SA license, shows an increase in the number of Attribution-only resources comparable to SA. This might suggest strong motivating factors in the use of free licensing in the Attribution category that should be looked at more closely. Perhaps the belief in a cultural commons is growing regardless of detailed copyleft legal mechanisms, and/or perhaps Attribution is a stronger currency in the exchange of intellectual property than the various legal mechanisms designed to govern it. It is a research project in its own right, but for this article it is enough to suggest that copyleft legal mechanisms may not be the strongest element in the growth to free cultural works, particularly OERs.

From 2001-2004 there probably wasn't an e-learning unit on the planet that had not discussed reusable learning object (RLO) theory. Some people became very caught up in the ill-defined and poorly understood "holy grail" for e-learning, and invested large amounts of time and money developing content that conformed to a range of reusable object standards in their Learning object projects (Wikipedia, 2007). The energy and commitment behind learning object development has waned considerably in recent years, to a point where it is a rarely talked about and generally rarely considered area in today's e-learning units. The rise in educational use of popular content repositories like Wikipedia and YouTube [http://youtube.com], and the vastly improved understanding of blogs, wikis, and the Internet generally, has led many to question the relevance and integrity of the concept of RLOs (see Wiley, 2001; Polsani, 2003; Downes, 2005; Seimens, 2004; Farmer, 2004; Jarche, 2005). Still, it is worth noting the functional requirements of a RLO if only to see why its relevance is questionable (see Polsani, 2003):

These desiderata are remarkably similar to the requirements of an OER. Or at the very least, an OER could be said to meet all these functional requirements and more. For an educational resource to be fully "open":

The popularity and emergent usefulness that socially networked media, Web 2.0, or social Web) have to learning should not come as any surprise. Contemporary learning theories and pedagogical practices have been influenced by social constructivism, and the relevance that social media has to that thinking should become increasingly obvious as more and more educators gain practical experience and critical awareness of learning through social media. Ivan Illich wrote of learning webs and envisioned a society empowered through the use of audio cassette tapes and the postal service. Illich could barely have imagined what is the case today, with the use of podcasts and other media, and should be happy to see his ideas proving true. Illich would probably have remained justifiably critical, however, as today's social media is only accessible in wealthy societies and little has been achieved to slow the widening gap in the now-termed digital divide. But the successes of social media in wealthy societies should be seen as a successful embodiment of Illich's vision for learning webs. While the formats and delivery mechanisms may be different, the concept remains essentially the same--give many people the ability to tell their own stories and ask their own questions to many other people, and socially constructed learning opportunities will emerge. Many engage in the almost daily practice of writing and answering emails, conversing through chat rooms and forums, publishing and watching video and audio, and collaboratively editing documents and media that are simultaneously being stored and archived publicly for others to access, learn from, and connect with. Informational and personal connections are being made through this social media, most of which creates an impressive opportunity for learning. But as yet educational institutions struggle to define themselves within this information and communication landscape and appear content with a wait-and-see stance.

Meanwhile new forms of educational institutions may be developing. The Wikimedia Foundation added Wikiversity to complement its suite of reference resources, and while it rapidly develops its technology, content and connections--with an average edit interval of 20 minutes (for example, http://en.wikiversity.org/wiki/Special:Recentchanges/)--the user group discusses its relationship to educational institutions and credentialism Wikiversity list archive May 2007. The Commonwealth of Learning has established a similar project called Wikieducator [http://www.wikieducator.org] that is proactively drawing in professionals and consultants to help with its positioning and is growing at a similar rate to Wikiversity.

It could be that Illich's vision is already happening, albeit through the use of sophisticated and still exclusive technology. With people empowered by the ability to connect and communicate with many others, perhaps new pathways to formally recognised learning will emerge from this social media and directly challenge those who simply wait and see.

The most exciting area to be involved with in educational development is Web 2.0. Some people think that like RLOs, Web 2.0 is another passing fad that will have little relevance in years to come. But unlike RLOs, Web2.0 is what it is because of the sheer numbers of people participating, and if it does not come to dominate education, it will not be because it is difficult to understand or implement, it will be because technology and user abilities will have developed even further. Already this move has been suggested with the term Web 3D, where participation in 3D virtual worlds is growing considerably--but that is another article.

Keats and Schmit (2007) explain Web 2.0 reasonably succinctly:

Over the past three-four years, a set of technologies and social phenomena have arisen on the Internet that are collectively referred to as Web 2.0 (Web two point oh) indicating that the World Wide Web has seen a set of important changes since its inception (version 1.0) which have turned it from an access technology into a participation technology. (n.p.)

Participation is the key. As Borsch (2006) puts it in "Rise of Participation Culture" (with reference to college graduates of 2006): "This shift in internet use from passive to active is at the heart of their digital behavior and can be summed up in one word: participation" (n.p.) The Pew Internet and American Life Project (2005) characterizes this change succinctly: "The Web has become the new normal." (n.p.)

But what is Web 2.0? Technically speaking it is the use of blogs; wikis; video, photo and audio sharing sites; forums, chats, and even email to develop what becomes socially networked media. As Michael Hotrum (2005) suggests in "Breaking Down the LMS Wall":

"All in all it was just a brick in the wall. All in all it was all just bricks in the wall." (Pink Floyd, November 30, 1979)

The Internet is independent of device (hardware or platform), distance, and time, and is well-suited for open, flexible, and distributed learning. Yet traditional online, distributed learning methods are anything but flexible, open, or dynamic. What went wrong? Parkin (2004a, 2004b) believes that we failed to appreciate that the Internet is a vehicle for connecting people with each other. We implemented LMS methods that imposed bureaucratic control, diminished learner empowerment, and delivered static information. "In a world hurtling toward distributed internetworking, e-learning was still based on a library-like central-repository concept." (Parkin 2004b, n.p.) Parkin suggests it is time to explore the true promise of e-learning, and to rework our ideas about how learning should be designed, delivered, and received. It is time to stop letting the LMS vendors tell us how to design learning. It is time to stop the tail from wagging the dog.

Others are seeing the link between participatory culture and some of the core objectives for education: People like Renee Fountain (2005) have prepared resources that describe wiki pedagogy; while Peter Rawsthorne (2005) looks for ways to apply learner-generated curriculum and content. With participatory culture arguably being the norm for a generation of people accustomed to socially networked media and online communication, so-called learner generated content will naturally develop. And this places educational institutions in a potentially hazardous predicament. What are the implications for an institution or a course within an institution when a large number of its students start blogging all that happens to them there? How can an institution and the teacher respond if and when they are exposed to both encouraging and discouraging information about their services and practices?

The response to this question is open participation, of course. We need teachers skilled and experienced with Web 2.0 technologies and communication methods so that they can participate at this level and offer balance to information that may come only from a student perspective. We need to engage in OER development and participate in open socially networked media and communication platforms. The alternative would be to engage in very measured and controlled ways, such as through a marketing department, or not to engage at all.

The inevitable conclusion is that educational organisations should develop capacity among staff and students to access, create,modify, and redistribute OERs, and to participate in socially networking them. Developing skills and practices along these lines will improve the efficiency and quality of their teaching and learning.

Here is the problem:

The following is a very typical situation experienced in many educational institutions:

Here is a solution:

This example represents the experiences of some teachers at Otago Polytechnic. Those who made an initial approach to the Educational Development Centre were exposed to a number of issues and ideas relating to OERs and open educational practices. Tentatively, a few developed the confidence to use and contribute content into the social mediascape; and some are beginning to present their own work as OERs. Subsequently, the networking opportunities afforded through this participation are creating a more sustainable practice of professional development that more directly meets their specific needs, as they begin to communicate with other professionals in their field who can offer context, advice, and ideas directly relevant to their subject area.

The role of the Polytechnic senior management cannot be understated in these initial successes. They permitted staff to explore and publish works; they permitted staff to work outside the learning management system that was being prescribed; they defended this exploration against internal critics and reactionaries; they actively researched notions of Web 2.0 and socially networked media in education and quickly recognised the potential benefits and wider issues. They are developing a revised intellectual policy that adopts the use of a Creative Commons Attribution license as a default position, but with options to restrict a resource if necessary. This simple feature within the policy retains the ability to protect their Internet protocols or restrict copying and reuse, but enables individuals to participate in the development of OERs and to adopt more open educational practices.

As mentioned earlier, in 2006, Otago Polytechnic established an Educational Development Centre to assist the institute in developing flexible learning programmes and staff training. Research into online learning has been allowed to refer to a wider range of options than LMS-centric practices, with social media becoming a growing focus in the Centre. As a result, the work of a small number of early adopters from a range of departments is observable through the following contributors:

This sample of work shows a number of instructors who are making gradual steps in socially networked media and gaining practical experience and critical awareness that will be valuable in the years ahead. These individuals communicate via an email list with others who have not set up a Web log but have interest in it nonetheless. They post general questions and answers, as well as items of interest, and occasionally organise informal face-to-face meetings to support each other's progress.

Currently the Educational Development Centre is leading collaborative developments of OERs on wikis. Recognising the critical aspect of the wiki, a large and active number of participants in the Centre went for already established platforms that were inviting open participation from people interested in developing educational resources. At the time there were the two major projects previously mentioned, which were attracting a large number of participants: Wikiversity and Wikieducator.

Wikiversity is a project under the Wikimedia Foundation and as the name implies, is a space for content that focuses on education (not just higher education).

Wikieducator is a very similar initiative but headed by the Commonwealth of Learning using the same wiki platform as Wikiversity: Mediawiki.

Both these initiatives are developing into major open educational resource projects, but the most notable difference about these compared to earlier open courseware projects like MIT's is that they use a wiki platform, which extends the principle of access to participation through collaborative editing, email lists, chat, and discussion forums for global users.

Otago Polytechnic's Educational Development Centre has been participating in both these initiatives to gauge the quality of activity behind each and establish what level of interest there is among Otago Polytechnic staff. Initial work on both initiatives has been largely encouraging with staff quickly recognising the benefits of open and collaborative authoring.

Benefits found in working on a wiki include:

Benefits of Wikiversity and Wikieducator:

Concerns:

This last concern relating to copyright may result in the Polytech having to set up its own wiki, a situation that is both disappointing and limiting in terms of collaborative development and networking opportunities. The key issue is in the choice in copyright on both platforms that is difficult to manage and in some instances impossible to honour. This conflict may ultimately exclude some level of development contributions from the Polytechnic, and arguably from most educational institutions.

Wikiversity uses the Gnu FDL and Wikieducator uses a Creative Commons Attribution-SA license. As explained earlier in this article, both these licenses allow modifications and redistribution of derivative works only if the resulting work is licensed with the same restriction. This legal mechanism is designed to ensure the continued growth of reusable content, but does it? As argued earlier, perhaps there are other things that encourage the growth of open content, namely, attribution; and any legal mechanism that is difficult and largely impossible to enforce is enough to prevent reuse and participation. Such is the case between Otago Polytechnic and the Wikiversity and Wikieducator platforms. While Otago Polytechnic is positioning itself to publish and contribute to the development of open educational resources, the license on those two platforms may prevent our participation. Otago Polytechnic cannot be certain what the range of its activities may be in the future, as would be the case with most educational institutions.

Situations that present difficulties when using copyleft resources:

There are other scenarios that present difficulties for an educational institution that begins to develop resources and practices based on mechanisms of copyleft. The requirement to redistribute derivatives from a copyleft artifact under the same copyleft restriction may be impossible to honour in these situations. In some instances, it may be possible to keep copyright and copyleft resources separate and release a remix under dual licenses, but where a direct derivative has been made and the distinction between the two have blurred, this management of dual licenses is impossible. Complications in copyright like these are simply impractical to manage, which is why an institution will inevitably base its collaborative efforts, resource sharing and sampling, and general open educational development on content that is licensed in such a way so as to require only attribution--in other words, Creative Commons Attribution. This license maintains the reusability of a resource in any given situation without restriction other than attribution. It benefits the institution by encouraging wide reuse and subsequent attribution, and this publicity may turn out to be of greater value than the availability of copyleft educational resources, especially if research indicates that OERs proliferate regardless of copyleft mechanisms and more because of the value of attribution.

It is likely that Otago Polytechnic OER developments will have to take place on its own wiki, which will use a Creative Commons Attribution license by default, and allow for other licenses to be applied if needed. Once content is developed to a sufficient level it will be copied into the Wikieducator and Wikiversity platforms for further development by people in those projects. It is not likely that the Polytech will be able to use any subsequent modifications that are made on those platforms due to their being made under a SA restriction, but we will at least be able to see the developments and consider future directions of our own resource developments, and we may also benefit from the social networking opportunities offered by those more global platforms.

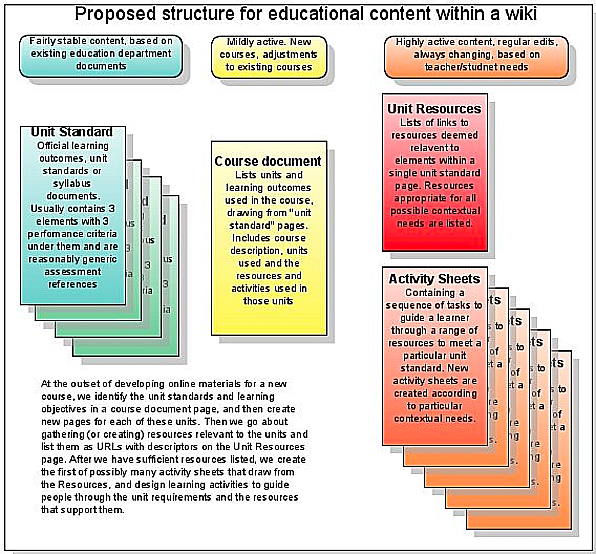

A structure for wiki content that we are considering may be seen in Figure 3. Activity pages will be the focus of the resource development and our local wiki will enable embedding and mash up of multimedia as much as MediaWiki Extension Matrix [http://www.mediawiki.org/wiki/Extension_Matrix/] and our own commissioned developments can achieve (see Blackall, 2007). We will continue to develop staff capabilities and confidence in the use and participation in socially networked media and work towards a high and identifiable quality of open educational resources that are made available through socially networked media channels.

Figure 3. Proposed wiki structure (Diagram made using Gliffy.)

We will perform these tasks through the staff development activities of the Educational Development Centre, such as The Designing for Flexible Learning Practice course, Networked Learning workshops, and informal support through facilitation of email discussion lists and face-to-face meetings. Also, programme development activities are facilitated through the Educational Development Centre but conducted by staff in the Departments who are developing their programmes. These developments are aimed at improving the flexible learning opportunities in a course, and so often, though not always, involve the use of online teaching and learning technologies. [Editor's note: Since the WiAOC in 2007, the author has updated progress at Otago Poly with an article for Penn State's World Campus (Blackall, 2007c)]

Through these activities we aim to develop better awareness amongst staff towards copyright, to lead that discussion into development of open educational resources, and to build a stronger presence of Otago Polytechnic on socially networked media platforms through the encouragement and support of staff participating in social media arenas.

Leigh Blackall works in Educational Development for the Otago Polytechnic and specialises in the use of socially networked media and communication and its relationship to socially constructed learning. He maintains the Learn Online Web Log [http://learnonline.wordpress.com] and facilitates the Teach and Learn Online eGroup. [http://www.protopage.com/teachandlearnonline/]. He and his wife, Sunshine, also design and develop multimedia educational resources.

Blackall, L. (2007a, March 15). My vision for Wikieducator. Learn Online. Available from: http://learnonline.wordpress.com/2007/03/15/my-vision-for-wikieducator/

Blackall, L. (2007b, August 18). Open educational resources and practices. Retrieved December 7, 2007, from http://wikieducator.org/User:Leighblackall/Open_educational_resources_and_practices.

Blackall, L. (2007c, November 29). Educational development at Otago Polytechnic. Terra Incognita: Exploring New Ground in Online Education. Penn State World Campus. Retrieved December 8, 2007, from http://blog.worldcampus.psu.edu/index.php/2007/11/29/educational-development-at-otago-polytechnic/.

Borsch, S. (2006). Rise of participation culture. Connecting the Dots/Marketing Directions, Inc. Retrieved December 7, 2007, from http://www.wsjb.com/RPC/V1/.

Commonwealth of Australia. (2007). Networks, connections and community: Learning with social software. Australian Flexible Learning Network/Val Evans Consultants. Available from http://www.flexiblelearning.net.au/flx/go/pid/377/.

Creative Commons Attribution License 3.0 Unported. (n.d.) Available from http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/3.0/.

Creative Commons Attribution-Non-Commercial 3.0 Unported. (n.d.) Available from http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/3.0/.

Creative Commons Attribution-Share Alike 3.0 Unported. (n.d.) Available from http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/3.0/.

Creative Commons [wiki]. (2007, December 5). License Statistics. Retrieved December 6, 2007, from http://wiki.creativecommons.org/License_statistics.

Definition of Free Cultural Works. (2007, February 27). Retrieved December 7, 2007, from http://freedomdefined.org/Definition.

Downes, S. (2005). What e-learning 2.0 means to you. [Audio recording of a talk given to the Transitions in Advanced Learning Conference in Ottawa, Canada, September 14, 2005]. Retrieved September 14, 2005, from http://www.downes.ca/files/audio/what_el2_means.mp3.

Fountain, R. (2005). Wiki pedagogy. Retrieved December 7, 2007, from http://www.profetic.org/dossiers/rubrique.php3?id_rubrique=110

Farmer, J. (2004, November 18). Beyond the LMS: Incorporated subversion. Retrieved December 7, 2007, from http://incsub.org/blog/index.php?p=75.

Gliffy, Basic Version. (2007). Gliffy, Inc. Available from http://www.gliffy.com.

Hotrum, M. (2005). Technical evaluation report 44. Breaking down the LMS walls. IRRODL, 6(1). Retrieved December 7, 2007, from http://www.irrodl.org/index.php/irrodl/article/view/212/295.

Internet Archive. (2001). Available from http://www.archive.org.

Jarche, H. (2005, September 6). Small (learning) pieces loosely joined. Learning. Retrieved December 7, 2005, from http://www.jarche.com/node/584/.

Keats, D & Schmidt, J. (2007). The Genesis and emergence of Education 3.0 in higher education and its potential for Africa. First Monday, 12(3). Retrieved December 1, 2007, from http://www.firstmonday.org/issues/issue12_3/keats/.

MediaWiki (2007, December 3). Extension matrix. Wikimedia Foundation, Inc. Available from http://www.mediawiki.org/wiki/Extension_Matrix/.

Meta-wiki. (2007). Meta-wiki.com. Available from http://www.meta-wiki.com.

Müller, E. (2005, September 12). Creative Commons: NC licenses considered harmful. Eloquence in Internet. Retrieved December 6, 2007, from http://www.kuro5hin.org/story/2005/9/11/16331/0655/.

Müller, E. & Hill, B. M. (2007, February 27). Definition of Free cultural works: Revision history. http://freedomdefined.org/index.php?title=Definition&action=history.

OCW Finder. (n.d.) D. Wiley. Available from http://ocwfinder.com.

Open Courseware Consortium. (n.d.) Available from http://www.ocwconsortium.org/index.php?option=com_content&task=view&id=16&Itemid=31.

Ourmedia. (n.d.) Available at http://www.ourmedia.org.

Paharia, N. (2005, February 25). License distribution. Creative Commons [blog]. Retrieved December 6, 2007, from http://creativecommons.org/weblog/entry/5293.

Parkin, G. (2004a). The tail is wagging the dog. Parkin Space Weblog. Retrieved January 5, 2005, from http://www.trainingzone.co.uk/news/parkin/.

Parkin, G. (2004b). E-learning adventures beyond the LMS. Parkin Space Weblog. Retrieved January 5, 2005 from: http://www.trainingzone.co.uk/news/parkin/.

Pew Internet and American Life Project. (2005, January 25). Report: Internet evolution. Retrieved December 7, 2007, from http://www.pewinternet.org/PPF/r/148/report_display.asp.

Polsani , P. (2003, February 19). Use and abuse of reusable learning objects. Journal of Digital Information, 3(4), Article No. 164. http://jodi.tamu.edu/Articles/v03/i04/Polsani/.

Rawsthorne, P. (2005). The effectiveness of learner stories. Retrieved December 7, 2007, from http://www.rawsthorne.org/bit/medit/ed6610/docs/PeterRawsthorne.IBRPresentation.pdf.

Seimens, G. (2004). Learning management systems: The wrong place to start learning. eLearnspace: Everything elearning. Retrieved December 7, 2007, from http://www.elearnspace.org/Articles/lms.htm.

Slideshare. (2007). Slideshare, Inc. Available at http://www.slideshare.net.

Top Sites (1996-2007). Alexa Internet, Inc. Retrieved May 2007 from http://www.alexa.com/site/ds/top_sites?ts_mode=global&lang=none.

UNESCO. (2002). Forum on the impact of open courseware for higher education in developing countries. Retrieved December 7, 2007, from http://portal.unesco.org/ci/en/ev.php-URL_ID=9110&URL_DO=DO_TOPIC&URL_SECTION=201.html.

Vest, C. (2002). A Message from the President. MIT. Retrieved December 8, 2007, from http://web.archive.org/web/20021014163054/ocw.mit.edu/.

Wikimedia Commons. (2007, November 19). Wikimedia Foundation, Inc. Available from http://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/Main_Page.

Wikibooks. (2007, May 10). Wikimedia Foundation, Inc. Available from http://en.wikibooks.org/wiki/Main_Page.

Wikijunior. (2007, October 29). Wikimedia Foundation, Inc. Available from http://en.wikibooks.org/wiki/Wikijunior.

Wikieductor. (2007, December 2). http://www.wikieducator.org

Wikimedia Foundation. (2007, December 8). Home. Wikimedia Foundation, Inc. Retrieved December 8, 2007, from http://wikimediafoundation.org.

Wikinews. (n.d.) Wikimedia Foundation, Inc. Available at http://wikinews.org.

Wikipedia: (2008, February 15). Ivan Illich. http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Ivan_Illich.

Wikipedia (2007, November 29). Open educational resources. Wikimedia Foundation, Inc. http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Open_educational_resources/.

Wikipedia: (2008, January 16). Social Web. http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Social_Web/.

Wikipedia: (2008, February 16). Text of the GNU Free Documentation License. http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Wikipedia:Text_of_the_GNU_Free_Documentation_License/.

Wikipedia: (2008, March16). Web 2.0. http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Web_2.0/.

Wikipedia (2007, 17 May). Learning Object Projects. Wikimedia Foundation, Inc. http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Learning_Object#Learning_object_projects/

Wikiquote. (2007, December 6). Wikimedia Foundation, Inc. Available at http://wikiquote.org.

Wikisource. (2007, December 6). Wikimedia Foundation, Inc. Available at http://wikisource.org.

Wikispecies. (2007, December 5). Wikimedia Foundation, Inc. Available at http://species.wikimedia.org.

Wikiversity. (2007, December 8). Recent changes. Wikimedia Foundation, Inc. Available from http://en.wikiversity.org/wiki/Special:Recentchanges/.

Wikiversity List (2007, May 30). [Topic:] Free online degrees? Pipermail. Available from http://lists.wikimedia.org/pipermail/wikiversity-l/2007-May/thread.html

Wiley, D. (2001). The Reusability Paradox. [Originally written for and hosted at the Utah State University.] Retrieved September 2005 via the Internet Archive's WayBack Machine. http://web.archive.org/web/20041019162710/http://rclt.usu.edu/whitepapers/paradox.html

Wiley, D. (2005, July 23). OCW Finder. Iterating Toward Openness. Retrieved December 7, 2007, from http://opencontent.org/blog/archives/175/.

Wordpress. (2007). Automattic, Inc. Available from http://wordpress.com.

YouTube. (2007). YouTube, LLC. http://www.youtube.com.

![]()

A list of bookmarks relevant to this article may be found at Blackall (2007b). For a complete list of bookmarks relevant to this topic, see [http://del.icio.us/leighblackall/OERP/].

For a recording and slides of the WiAOC presentation, see [http://flickr.com/photos/leighblackall/sets/72157600223371021]. Please join the WikiEducator mailing list at http://groups.google.com/group/wikieducator/ to help coordinate the development of WikiEducator content, structure, and technology. We are experimenting with a new discussion system. Please see LiquidThreads for details: [http://wikieducator.org/LiquidThreads/ ].

|

© Copyright rests with authors. Please cite TESL-EJ appropriately.

Editor's Note: The HTML version contains no page numbers. Please use the PDF version of this article for citations. |