March 2007

Volume 10, Number 4

| Contents | | | TESL-EJ Top |

|

March 2007

|

||

|

nyu.edu>

nyu.edu> mun.ca>

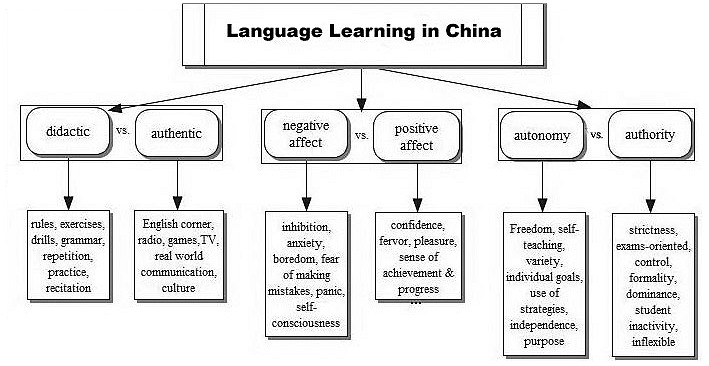

mun.ca>This study explores the Language Learning Experiences (LLEs) and beliefs of six non-native speaking (NNS), English as a Foreign Language (EFL) teachers in China. Data collection involved an online questionnaire, an asynchronous focus group, as well as individual online interviews. Findings were presented as profiles of the six cases. Cross-case analysis using open and axial coding resulted in the identification of three categories of concepts as follows: positive versus negative affect in language learning; authority versus autonomy; authentic versus didactic language learning. The tensions within and between the categories and concepts point to the complexity of EFL teaching and learning in China.

Teachers' experiences or memories of their days as students may include a repertoire of teaching strategies, assumptions about how students learn and a bias toward certain types of instructional materials (Johnson, 1999). Bailey et al. (1996) found that teachers' learning experiences not only influenced their criteria for judging things like successful or unsuccessful language learning, but also strongly influenced the way they taught. Johnson (1999) argues that most language teachers have both formal and informal language learning experiences and those experiences can have a powerful impact on their beliefs. However, "this in itself can create conflicting beliefs" (p. 34) for language teachers because they may have few concrete models of how to recreate more positive informal language learning experiences for their own students in their own classrooms.

Over the last 15 years, the concept of belief has gained considerable attention and research into the area has taken many directions in several key areas of interest to ELT (English Language Teaching) professionals (Borg, 2001). This research ranges broadly from investigations of language learners' beliefs (e.g., Carter, 1999; Cotterall, 1995, 1999; Horwitz, 1988, 1999), language teachers' beliefs (e.g., Bailey et al., 1996; Johnson, 1999), a comparison between the two groups (e.g., Kern, 1995; Kuntz, 1997; Peacock, 1999), to the exploration of the relationship of teachers' beliefs to their teaching practice (e.g., Borg, 1998; Kagan, 1992; Kennedy, 1996; Raymond, 1997; Woods, 1996). A number of studies examining pre-service teachers' beliefs identified how teachers' prior in-class learning experiences influenced their beliefs (e.g., Armaline & Hoover, 1989; Brown & McGannon, 1998; Horwitz, 1985; Johnson, 1994; Tillema, 1995). However, few empirical studies have focused on in-service/practising teachers (Peacock, 2001).

Compared to the amount of literature about native speaking (NS) ESL teachers' beliefs or personal language learning experiences (LLEs) in western countries, there are far fewer studies in pertinent research domains of nonnative speaking (NNS) EFL teachers. The large number of NNS language teachers around the world "face different challenges than those teachers whose subject matter is their own first language" (Bailey, Curtis & Nunan, 2001, p. 111). Given the different social-cultural backgrounds in which they learn and teach the target language, NNS EFL professionals are unlikely to share the same personal experiences or beliefs as NS ESL teachers. China, being one of the leading sources of immigrants to North America in recent years, is a country with a large number of NNS EFL teachers. The lack of attention to this group may not only result in a failure to understand current practice in TESOL (teachers of English to speakers of other languages), but also to understand and educate Chinese immigrants in those countries.

The purpose of the study reported on in this paper was to identify the LLEs and beliefs of Chinese EFL teachers in China. Additionally, we sought to identify concepts common to both their LLEs and their beliefs about teaching EFL in China. To achieve this goal, we completed individual case studies and subsequent cross-case analyses of six Chinese teachers of EFL. The case study approach was chosen because neither the language learning nor teaching experiences of this population under study can be "readily distinguishable from its context" (Yin, 1993, p. 3).

We chose a comprehensive university in the central part of China to be the site of the study. The sampling frame included all the in-service NNS EFL teachers in the Faculty of Foreign Language and Literature in the target university. Using email, we sent a request for participation to all 64 members in the faculty. Twelve teachers replied and provided their informed consent. One participant left the study during the administration of the online questionnaire while another left in the middle of the focus group. Six participants completed all three phrases of the study. It is these six who are profiled.

Data collection lasted for two months and included an online questionnaire, an asynchronous, online focus group, and email-based individual interviews all conducted within a WebCT[1]shell. We piloted the questionnaire with five EFL teachers from China one month prior to its administration. As a result of the pilot, some changes were made in the order of the statements of beliefs. Statements were no longer grouped into different areas such as the beliefs about the nature of English and the beliefs about the teaching program and the curriculum. We administered the online questionnaire for a period of two weeks immediately after recruiting teachers. The first part of the questionnaire focused on background and demographic questions. The second group of questions were open-ended and designed to elicit information about individual LLEs. An example of one such question is as follows: "If applicable, describe any experiences of language proficiency improvement in your teacher education program. How did these experiences help/not help your language learning and/or teaching?"

The main part of the questionnaire contained 26 statements synthesized from three existing and tested questionnaires (see: Allen, 2002; Horwitz, 1985; Johnson, 1992). The statements addressed beliefs related to four areas: the nature of English; EFL learning; EFL teaching and; beliefs about their teaching program and the curriculum. Teachers could check any of the statements that corresponded to their personal beliefs. In addition, we included an open-ended question at the end inviting them to select five of the 26 statements that best reflected their personal beliefs about language learning and teaching and to explain why they selected those statements.

After completing the questionnaire, teachers participated in a six-week long online focus group using the WebCT discussion forum. The online focus group of this study largely resembled its traditional forms, except for the need to transfer some of the qualities online (Mann & Stewart, 2003). We asked four questions in the forum one after the other in the six-week period. Teachers had approximately one and a half weeks to reflect and respond to each of the questions. An example of a focus group question is as follows: "Regarding your in-class language learning experiences, were there any experiences that impressed you? Do you think that the methods your teachers used were effective? Why? Would you have preferred a different approach? Why?"

When participants know they are being studied and particularly in a cooperative context with other members, "they may alter their presentations of self to fit the situation" (Jackson, 2002, p. 181). Some participants might as well, "for their own reasons . . . choose not to express to the entire group" (Murphy, 2000, p. 116). It was for this reason that we also incorporated a more formalized system of individual interviewing into the study. These one-on-one interviews gave teachers a different context in which to make explicit and articulate more privately their experiences and beliefs.

We conducted asynchronous individual interviews simultaneously through e-mail correspondence using a 'reply privately' option available in the discussion forum within the WebCT shell. Questions were non-standardized and tailored for different individuals based on an on-going understanding and analysis of their responses to the questionnaire and the focus group questions. The questions aimed at "clarification and amplification of interesting points, with appropriate probing, and targeted questioning" (Gaskell, 2000, p. 45). An example of one question is as follows: "Could you please explain in detail what you meant by 'the shortcomings of the EFL system in China'?"

We integrated ongoing analysis into each phase of the data collection. Examining responses to the online questionnaire for 'cues' led to the particular topics and questions in the focus group. In the context of the focus group, it was the ongoing analysis of teachers' responses that led to new topics and questions. Finally, the early analysis of the focus group responses also led to probing in the individual interviews. Once we collected all the data, we organized them into manageable formats. Following the suggestions given by Creswell (2005), we developed a matrix to help the organization. All the LLEs and beliefs of one individual were synthesized respectively. Analysis then involved focusing on each individual case using the sentence as the unit of analysis. We began with open coding to break down, examine and compare the data and to identify important concepts. We followed with axial coding to create connections between codes and to form categories (Strauss & Corbin, 1998).

In our presentation of the profiles of the LLEs and beliefs, we aim to convey as much as possible the character and voice of the individual. For this reason, we cite their actual words where appropriate. We present the profiles chronologically for each individual in order to capture the continuous nature of their experience and to interweave their beliefs. The six teachers profiled are as follows: Jeff, Laura, Linda, Daisy, Vincent and Roy.

Jeff

Jeff is currently a Ph.D. candidate in Canada. He had two years of full-time EFL teaching as well as four years of past-time tutoring experiences in China. He currently tutors some ESL as well as EFL students online. Jeff "used to be a very slow learner" in English and "had difficulty in even memorizing the simplest spelling." "Like most other EFL learners in China," he was, "afraid that making mistakes would cause [him] to lose face." However, with the help of his first English teacher, who he remembers as "very energetic and responsive," English became "easier and much more interesting" and he began making "huge progress," "became one ace student in English" and developed a "fervor in learning English." This improvement inspired Jeff and helped him "overcome the anxiety and nervousness" he had when learning English in the beginning.

Language learning in university involved "more freedom" and "became much more extensive and students were exposed to various learning activities." Jeff attended and was "intrigued" with lectures given by native-speaking teachers whose pronunciation gave him "a perfect example of native accent to imitate." Realizing "the insufficiency of in-class EFL learning," Jeff actively took part in various English speech contests and debates, listened to radio programs, played English video games, watched English movies, and participated in informal oral-English classes such as English Corner, "a place where students come in to talk in English casually."

Jeff considers English Corner as a "relaxing environment for language learning" and for "lowering the pressure one might encounter when speaking English." At the same time, he recognizes a disadvantage to the "casual" approach of English Corner: " . . . no one is supposed to notify you when you make some mistakes in English, and as time goes on your mistakes can become unchangeable bad habits." In general, he believes that the various out-of-class LLEs are "very important in terms of understanding of the cultures behind the language." At the same time, he credits the solid background he developed in grammar and vocabulary in high school with helping him "build up more confidence in EFL learning."

While Jeff believes it is "extremely important" for Chinese EFL learners to speak English with native-like pronunciation, doing so "is [a] thousand times more difficult in China than in English-speaking nations." He is critical of EFL teaching in China because "students in China do not receive adequate training in communication skills," and in many cases, "students are not even allowed to have or think about their actual goals of EFL learning." In addition, Jeff believes that EFL teaching in China was, and still is, "restrictive," "formal," mostly "geared to exams," and based on "outdated textbooks" as well as "limited authentic materials." As a result, students, "gradually lost their activeness in language learning . . . they were so used to being taught what to do and what not to do, what to learn and what not to learn." Jeff disfavored the strictness of in-class instruction as "teachers would be authoritative and would play a dominant role" while students "were supposed to pay attention . . . obey rules, and not ask questions unless teachers said so."

Laura

Laura spent more than 15 years teaching EFL in China. Immediately following the administration of the online questionnaire, she went to the United States as a research scholar. While in the States, she completed the discussion and interview parts of this study. When Laura began studying English in junior high school, there was a lack of sufficient teaching and learning resources. Students had only one or two reference books as well as textbooks that "focused on drills, grammar rules and exercises." All of Laura's EFL high school teachers "attached great importance to grammar teaching." Chinese was the only language used in class. Teachers "translated the drills one by one and the text sentence by sentence." Students were required to do "a lot of homework on grammar." Although such exercises were "very boring," Laura thinks they helped her "to grasp the English grammar well."

Laura was interested in learning English from the very beginning and therefore worked very hard at it. She recalled her English teacher who offered her great help at the time and often lent her some authentic books and tapes. However, because of the lack of learning resources, Laura had very few opportunities for out-of-class language learning during her secondary schooling except for radio.

When Laura entered university initially, English was not her major. All EFL teachers were Chinese and she had no "oral classes" and "didn't know how to speak English at all." Once she changed her major to English, she got more comprehensive training in the target language and was able to take courses offered by native-speaking teachers. When she had just become an English major, she felt very "self-conscious," worried about "making mistakes" and being "looked down upon by classmates" and, as a result, "always sat mute" in class. After a period of adaptation and with opportunities to "practice English more and more" during out-of-class activities, she gained confidence and began to enjoy her English classes. She read Bible stories in English, practiced oral English with a friend, listened to the radio, socialized with English speakers, watched English movies, joined in English Corner and audited lectures presented in English.

Laura believes that "the purpose of English learning is to communicate with others in English . . . . To only grasp the grammatical rules is useless." She further believes that, in English-speaking countries, it is "very easy for the English learners to find a person to practice English with." In this regard, Laura noted: "problem-solving is an important part in EFL teaching and learning . . . . If learners don't know how to use the target language to solve problems, English learning is meaningless and useless."

Laura believes that "only with authentic materials," can EFL learners "learn how to use the language in real, authentic situations." Teachers should devote some time to teaching students how to use specific communication strategies such as circumlocution, approximation and gestures. In addition, as language learning is for communication, teachers should focus on what students are trying to say instead of how they say it and "when students make oral errors, it is also best to ignore them, as long as what they are trying to say can be understood."

Laura noted that "learning English by oneself is very boring" while learning with a group is "full of fun and will be very interesting." For this reason, she values studying English "in a team" and developing "collaborative skills" whereby learners "can help each other, encourage each other and thus make progress together." Although Laura had various out-of-class LLEs, she believes that in-class learning is "the most important part of the language learning, especially for Chinese students." In-class learning provides a "foundation" or "skeleton" for learning more "beyond class." She argues: "besides grammar learning, teachers should give students more chances to speak, listen to and use the language." She added: "more output can help learners to be more active in language learning." Likewise, students should not be "afraid of making mistakes."

Linda

Linda has taught EFL in a Chinese university for 16 years. Meanwhile, she has been doing some administrative work in the faculty for more than five years. Linda's first EFL teacher soon found that she was a quick learner of the language. She took part in an English contest and won the first-class award. She was "encouraged a lot" and "began to believe that [she] had some talent in English learning." She had very positive memories of her first EFL teacher, who had "relatively standard English pronunciation" and was very kind to her. In contrast, in senor high, classes focused on grammar and vocabulary learning. Her new teacher was "not so lovely" because she "always wrote the grammatical rules on the blackboard and asked us to put them down as well in our notes."

During the six years in secondary school, Linda "never had the chance to even listen to an authentic tape" but "only followed [her] teacher's pronunciation of the target language." As a result, when entering university, she soon realized that her "oral English was not as good as" some other students and she became less motivated. She majored in English at university but remained very shy even in the oral English class offered by native-speaking teachers. She noted that she spent her time in the oral English class "in panic: Only a few of us who were good at [English] speaking enjoyed it . . . . Most of us kept silent or spoke short, broken English in class."

Linda was worried about her speaking and listening abilities and was even too anxious to follow her uncle's advice to listen daily to BBC radio programs or to materials he gave her. She did not think that she could catch up with the top students in a short period. Her anxiety continued even after she graduated from university. Her new identity as an EFL teacher soon forced her to shrug off her timidity and communicate in the target language. The experiences of "standing behind the podium" proved to be her "most valuable out-of-class experience." When recounting this experience, Linda remarked: "once I opened my mouth, I found that I was not a very slow learner in English speaking or listening. I gained my confidence."

Linda believes teachers should "encourage students to be engaged in communication rather than pay attention to grammar." Otherwise, as Linda remarked, "students can not enjoy English learning and they will feel frustrated after learning for many years but fail in real communication." She believes that with an overemphasis on correction, "students will lose confidence in themselves and retreat from the class." On the other hand, however, Linda believes that the grammar-translation and communicative approach play an "equal role" in EFL teaching because of their advantages and disadvantages. She noted that, "Whether it is a black cat or a white cat, as long as it can catch the mouse, it is a good cat. - coined by Deng Xiaoping." What Linda considers important is that, "teachers must follow the prescribed curricula in a relatively strict way. Otherwise, the students cannot improve their competence in the target language comprehensively."

A good EFL teacher needs to "interact with students very often and recommend to them various ways to improve English." In addition, a good EFL teacher should encourage students to be more "active and out-going" and "help them get rid of their foreign-language-phobia." Native-like pronunciation is important in EFL learning and teaching. At the same time, however, it is important to encourage students "to speak more, to be original, and to be creative." Linda justified this belief as follows: "We are not training broadcasting announcers. We teach students English because we want them to exchange their ideas with people all over the world." In general, Linda remarked: "how to motivate students to learn English is a big problem in EFL teaching."

While she believes that reading is important, she also emphasizes the role of listening to authentic materials especially when the learner "lives in a country where not too many people use English as an official language or even as a second language." She therefore posits that the learning of listening and speaking in the target language is "the biggest obstacle" for Chinese EFL learners. Students may not have access to audio materials or may not have the time to access them "due to heavy classwork and homework." She believes that the reform of the exam-oriented education system "is the most urgent for any course's teaching and learning, particularly for EFL teaching and learning". She commented that, "The English test for the college entrance exam only gives 20 scores for listening, naught for speaking. Under this circumstance, why should college candidates make great efforts in improving their listening and speaking? "

Vincent

Vincent has 14 years of EFL teaching experience in China. He described his first experiences of learning EFL in junior high school as "totally controlled by teachers with focus on analysis of texts and explanation of language points. There was no use of the target language in class. Listening and speaking was virtually ignored." In the last year of his study in secondary school, Vincent "formally turned to English as a major, in an effort to pass the College Entrance Examination." To achieve this goal, he began to learn English grammar systematically by himself and did relevant exercises at the same time. The pleasure that learning grammar brought him was "even greater than that from reading a fascinating novel or watching a gorgeous movie." His "excellent command" of English grammar gave him "a solid foundation" from which he benefited in later study.

He continued his EFL learning as an English major in university. The in-class learning experiences were similar to those he had in high school, with teachers at the center and analysis of texts and explanation of language points as the focus of teaching. During the four years in university, Vincent spent more time learning the language autonomously after class. He memorized a large amount of vocabulary and phrases as well as expressions. He read more extensively and, by listening to BBC radio, his listening ability "improved dramatically at the same time." Although Vincent also practiced his oral English with both native and non-native speakers, he was "much less motivated" by such activity. When recounting his LLEs, Vincent noted that verbal ability is an aspect ignored in his learning.

After working as an EFL teacher, he improved his proficiency in the target language by himself. While teaching, he learned a lot from analyzing "the reasons, characteristics and regularity of different errors" made by his students in their writing practice. The experience also helped make his instruction of EFL writing "much more efficient." Vincent took an in-service leave and had one-year learning experiences in an English speaking country. He remarked that he was "highly motivated" in such "natural learning." Besides "attending lectures," "exchanging academic views" and "communicating daily with native speakers," he had other language immersion experiences in this period as well.

In relation to his LLEs, he observed the following: "although I had a large vocabulary [in English], I could not speak the language freely. I can write correctly but not satisfactorily." He advocates a "grammar-translation teaching approach" as it contributes considerably "to the cultivation of students' writing and reading skills." Additionally he believes that "it is very important to create a natural learning setting in the classroom so that the learners will feel more motivated instead of being inhibited in using the language." He justified a strong belief in the value of "autonomous learning and individualized learning." He remarked: "I achieved more and enjoyed more out of class than in the classroom, which most probably resulted from my character since I taught myself more easily and quickly than others did me."

He noted that, like "the majority of Chinese EFL learners," he is "the victim of the traditional in-class language learning in China." This learning was characterized by "strict discipline and inflexible procedures." He explained:

"I received little attention but rather, regular attention was required. My teachers, all forged in the Cultural Revolution, looked stern and I had to absolutely follow their teaching. This teacher-centered learning could only be a one-way communication; it concentrated on form and didn't encourage or permit free use of the language to exchange messages. I could neither communicate nor figure out my own ideas. I felt extremely bored and inhibited."

He concluded as follows from these experiences: "my in-class learning experiences showed me that if classroom teaching is too formal, learners will be less motivated and less desired to communicate and this will inevitably result in lower efficiency in language learning."

Daisy

Daisy has 16 years' experience teaching EFL in China. For the first five years, she taught in a high school whereas she now teaches at a university. Daisy remembers that her teachers used to urge students to recite everything they learned: "drills," "texts" and "many grammar rules." Yet, she was "so interested" in the target language that she would "like to follow whatever teachers asked [students] to do." She did not have any out-of-class English learning experiences in junior high school and textbooks were the only learning resources available. In the final year of high school, she watched a popular English program on TV every day after class. Once she got to the university level, she realized that she "owed a great deal to this program" because it helped her attain "high marks in listening comprehension." It also helped her learn "how to communicate with others under different situations in [the] real world."

Her LLEs after she enrolled as an English major in university were "quite different" from those in high school. It was the first time she had contact with "foreigners," experienced English as the only language used in class, watched original English films or listened to radio programs. The periods of class during which she was "exposed to the real world of native-English" were "the happiest time" for her. She remarked: "I liked it, not only because I could listen to native English, but also because in this way I got to know the outer world, how people felt about the world around them." She reacted positively to an oral English class led by native-speaking teachers which she found interesting and amusing as students were divided into groups and talked freely on given subjects.

Daisy believes that the goals of EFL learning in China should be "to communicate with English speakers smoothly and freely as well as to have an access to the understanding of different cultures." She also referred to the importance of group work: "By group work, I learned to communicate with my fellow classmates; I learned to listen to what others said, and I learned to cooperate with others." Daisy noted that she insisted on using the target language in her instruction even if students could not understand and she had to translate her words into Chinese afterwards. She believes that, in this way, her students can be provided as much input as possible in the target language. While she recognizes the importance of grammar, Daisy is somewhat uncertain about its role in some contexts:

"When I could communicate well with the students, I had to tolerate their bad grammar mistakes. While they could write well with little grammar mistakes, I had difficulty in communicating orally with them in English. What is the best way to balance between listening, speaking skills and grammar mastering in EFL learning? What is the best way to deal with this in EFL teaching?"

Roy

Roy has taught EFL in China for more than 20 years. When Roy began to learn English in junior high school in a mountain region, students "had nothing except very simple textbook with only one sentence in each unit." Moreover, sentences inside the textbooks were translations of the quotations from Chinese president Mao Zedong's speech. However, Roy was "deeply moved" by his teachers' hard work and "decided to follow their examples" to be an EFL teacher.

Roy worked very hard at English in secondary schooling because his first EFL teacher "was strict with his students" and he "was afraid of his serious eyes in the class." Discipline was emphasized and students would be punished if they "made trouble in class." In spite of this approach, Roy "was quite happy with the in-class language learning experiences" during the time because the teacher "was able to make his class vivid and lively" and "All that he did in class aroused my interest in and curiosity about English."

Besides learning English in the classroom, Roy read texts aloud every morning and repeatedly practiced new words, phrases and sentence patterns in the evening. When he entered senior high school, "things were getting better" as he began to study in a town. Roy bought himself an English dictionary and used it to look up new words and phrases he came across during his out-of-class learning. With the dictionary, Roy "read simplified English stories" in which he "saw a different world far away from China." In university, Roy majored in English education. He spent more hours reading in English and, after class, shared "highlights of English stories" as well as a radio with classmates.

Roy believes that the main purpose of learning a foreign language is to "use it to do things," to "communicate with its users and gain new, useful information." EFL teaching therefore should focus on communication rather than on grammar. Students need to pay more attention to what they are trying to say instead of how to say it. Teachers should use English as the dominant language in instruction and devote some time to teaching students how to use specific communication strategies such as circumlocution, approximation and gestures.

As an EFL teacher, Roy believes in the importance of helping his students understand "what English is [like] in real society" by offering them opportunities to "access authentic English by allowing them to listen to the tapes and watch more movies in class and after class." He argues that this role is essential because "Chinese students are exposed to relatively small amount of spoken and written [materials in] English and small number of native speakers." Moreover, Roy believes EFL learning is also "quite different from learning other subjects" because of the importance of authentic materials in such learning. He intends to train his students to become "active, independent and purposeful learners of the target language." In addition, Roy firmly believes in the importance of learner autonomy in EFL learning. He referred to such learning as 'self-teaching' and "awareness of learning." He also noted that "adults need to learn the way of self-teaching . . . [because] class at schools is limited . . . out-of-class [learning] is endless."

The six profiles present a diversity of experiences and beliefs. In spite of this diversity, common concepts are evident both within each individual case as well as across cases. A further, more important commonality both within and across cases is that groups or categories of concepts appear in relation to each other as follows: positive versus negative affect in language learning; authority versus autonomy and; authentic versus didactic learning experiences.

Within and across all profiles are multiple references to affective factors such as motivation, dedication, enthusiasm, confidence, interest, satisfaction, enjoyment and pleasure. In contrast to these are the more negative factors that the teachers associated with language learning: fear, anxiety, nervousness, lack of confidence, boredom, self-consciousness, worry, shyness, inhibition and frustration.

These concepts are not separate from each other but are linked. For example, Jeff associates high motivation (e.g., a "fervor in learning English") and overcoming anxiety and nervousness with having made "huge progress." Likewise, he links confidence with learning grammar. Like Jeff, Vincent also enjoys learning grammar. In fact, he enjoys it more than other activities. At the same time, Vincent was also highly motivated by out-of-class opportunities in a natural environment and associates this type of learning with more enjoyment and success. What makes him feel so positive about out-of-class learning is that it appeals to his "character" of an autonomous learner who believes he is his most effective teacher. Roy associates enjoyment with "in-class language learning experiences" because of his experience with a motivating teacher.

Unlike Jeff who links his confidence with grammar, Laura's confidence increased with opportunities to improve her speaking abilities in out-of-class activities. She links interest with group, as opposed to, individual learning. Daisy, along with Laura, associated her "happiest" moments with interaction with the "real-world." She also referred to the motivation and enjoyment of conversing in groups. Linda associates her increase in confidence with opportunities to speak and listen in English.

In all cases, motivation and enjoyment appear to be linked with a sense of achievement with either individual, in-class learning situations and a focus on grammar or with out-of-class situations associated with speaking and listening in group contexts. Vincent's case is different in that his motivation, enjoyment and sense of achievement relate to autonomous learning which he associates with out-of-class contexts.

In relation to the negative emotions associated with language learning, a common theme was the fear of making mistakes and of subsequently losing face. That fear generated anxiety, worry, panic and self-consciousness. In some cases, it resulted in inhibitions, extreme shyness or a decision not to speak in English. The mistakes related to not having good pronunciation specifically or to speaking and listening abilities generally. The mistakes also related to weaknesses in grammar. In Roy's case, fear of his teacher actually motivated him to work harder. Linda relates boredom to learning by oneself whereas, for Vincent, the boredom and inhibition come from a lack of control over his learning.

Another category of concepts that emerges from the profiles opposes authority on one hand and autonomy on the other. The concepts associated with authority are control, dominance, rigidity, strictness, formality, student inactivity and passiveness as well as an exam-oriented focus. In comparison, out-of-class learning is most often linked with flexibility, autonomy, versatility, collaboration, independence, freedom, and a focus on individual needs and individual goals.

The references to autonomous learning experiences are common throughout the profiles. They are often, but not always, associated with out-of-class learning experiences. In fact, Roy refers to the role of self-teaching and awareness of learning in order to take advantage of the limitless possibilities offered by out-of-class learning. The opportunities are often but not exclusively associated with opportunities to improve skills such as speaking and listening skills not normally well-developed in the classroom situation. Vincent's autonomous LLEs are somewhat different from those of others as he focused largely on independent grammar study, error analysis, memorization of vocabulary and expressions in addition to reading and listening to the radio and participation in English immersion experiences. He also exemplifies the autonomous learner by considering himself his best teacher.

Autonomous learning was linked to student-centered learning. Linda believes in teaching strategies to students and providing them with more chances to speak, listen to and use the language. Similarly, Linda believes a good EFL teacher is student-centered, interacts with students, recommends ways to improve their English and encourages them to be active, to speak and be original and creative. As an EFL teacher, Roy believes students should be "active, independent and purposeful learners of the target language."

In contrast to the concept of autonomy is that of authority. The authority is primarily linked with the Chinese education system. This authority is characterized by a lack of opportunities for students to set their own goals as well as teaching that is "restrictive," "formal" and mostly "geared to exams." The concepts associated with students are a passivity or lack of activeness characterized by their being taught what to do and what not to do, what to learn and what not to learn. Students pay attention, obey rules and do not ask questions without teacher prompting. The teacher plays an authoritative, commanding, stern, strict, controlling and dominant role. Discipline is strict, procedures are inflexible, classroom teaching is too formal and communication is one-way. Vincent described this approach as boring, unmotivating and inhibiting.

Others like Daisy accepted this authority because they were so naturally interested in learning English that they were willing to follow the teacher. In the case of Roy, he was so afraid of the serious eyes of his teacher and, at the same time, found his teacher so engaging, that he worked hard, was happy and motivated. While Linda believes that the Chinese system needs reform in order to be less exam-oriented, she nonetheless believes in the value of strictly following the prescribed curricula to ensure comprehensive language development.

A final but equally important category opposes authentic versus didactic language learning. The profiles provide insight into the contrast between and the role played by each type of learning. However, while the teachers appear to have adequate exposure to didactic learning experiences, their exposure to authentic experiences appears more problematic and more difficult to achieve. While they appear in opposition to each other, the teachers do not appear to advocate one approach without the other.

Across profiles, authenticity is most often associated with opportunities for exposure to the language outside of class with native speakers whose pronunciation provides perfect examples to imitate. The types of authentic activities highlighted in the profiles include attending lectures by or socializing with native-speaking teachers, taking part in various English speech contests and debates, listening to radio programs, playing games, watching movies, and participating in informal, casual and relaxing oral-activities such as English Corner. Authenticity also relate to exposure to the actual culture of English speaking people. For some individuals, these types of activities played an important role in terms of building confidence in language learning.

For Laura, authentic communication is the purpose of language learning and only with authentic materials, can EFL learners "learn how to use the language in real, authentic situations." Authentic learning was also associated in some cases with social learning. For example, Laura expressed clear and strong beliefs in favor of group, team and collaborative opportunities. Like Laura, Roy believes in the importance of exposing students to what English is like in real society. In fact, he argues that the importance of authentic materials is what makes learning EFL learning different from other subjects. As well, Linda believes that, to enjoy and to succeed in EFL learning, students need exposure to communication as opposed to grammar.

However, Roy, like the other teachers, recognizes that, while exposure to authentic materials and authentic communication is important, it is difficult to achieve in a Chinese context. The lack of easy access to authentic materials and opportunities for communication is, as Linda sees it, "the biggest obstacle" for Chinese EFL learners. Laura notes that, in English-speaking countries, it might be easy for EFL learners to find English speakers to communicate with. However, in China, it is more difficult.

In contrast, there is little shortage of exposure to didactic as opposed to authentic language learning. The didactic activities described by the teachers focused on drills, grammar rules and exercises, translation and a general emphasis on grammar teaching with Chinese as the language of instruction. Laura remembers having to do a lot of homework on grammar. Vincent describes a focus on analysis of texts and explanation of language points. Daisy remembers reciting drill, texts and many grammar rules. For a certain time, Roy's only materials were books with translations of quotations from the former Chinese president.

While the teachers advocate exposure to authentic materials and activities, they nonetheless value a didactic and analytical approach to language learning. Laura concludes that in-class study of grammar provides a foundation or skeleton. Linda argues that these two types of learning should have an equal role. While Jeff valued authentic communication in English Corner, he is also critical of the lack of attention paid to errors in that context. Laura found the emphasis on practice and drill boring but nonetheless believes it helped her to grasp the English grammar well. Jeff credits his background in grammar and vocabulary with helping him build up more confidence in EFL learning. Similarly, Vincent also believes that his command of English grammar gave him a solid foundation. Furthermore, he derived great pleasure from an analytical and didactic approach to the study of the language that involved memorizing large amounts of vocabulary.

The three categories and their related concepts are summarized in the following figure.

We are limited in this study to these six cases. For this reason, we cannot assume or infer that the experiences or beliefs of Roy, Laura, Linda, Vincent, Daisy and Jeff are typical of the LLEs or beliefs of other teachers in China. Furthermore, among these six cases, Jeff has been studying in Canada for years. Vincent had short-term professional development experiences in an English-speaking country while Laura embarked on her journey as a research scholar in the United States when the study began. As Zhang (2000, 2001 & 2003) noted, language learners who have study-abroad experiences may have different levels of anxiety as well as language learning strategies from their counterparts who only have LLEs in their home countries. Jeff, Vincent and Laura's reflections on their past LLEs as well as the articulation of their beliefs about EFL teaching and learning might, therefore, be influenced by the change of studying or working environment. For example, Jeff's beliefs about the relative ease of having native-like pronunciation in native-speaking countries, may be a result of his study-abroad experiences like Laura's beliefs about the ease of English learners practicing the target language in English-speaking countries.

Nonetheless, it is interesting to note that, although participants in this study had various personal experiences, their reflections on past LLEs and beliefs about EFL teaching and learning have much in common. Some of these findings, which are common across cases, also validate concepts previously treated in the literature related to teaching and learning in China. For example, Bond (1996) discussed the importance in China of losing face or one's status in relation to others. Tsui (1996) found that Chinese students are discouraged from openly questioning or criticizing because they are afraid of being wrong and subsequently losing face. Lee (1996) described the important role that exams play in Chinese culture and society. Oxford and Anderson (1995) argued that the Chinese learners prefer a style of learning that emphasizes rules and grammar. Ho and Crookall (1995) observed how some aspects of Chinese culture served as "impediments to autonomy" (p. 241). Salili (1996) commented on the lack of creativity and original thinking among Chinese students.

The contribution of this study is two fold. On one hand, the six cases present an opportunity to appreciate how concepts common in the literature on language learning such as authenticity, autonomy and affect, manifest themselves in real-life contexts. On the other hand, and perhaps more importantly, the six cases reveal the complexity of the concepts and the tensions that exist within and between them. The examples from the literature cited above portray a somewhat one-dimensional image of Chinese learners. What our six cases reveal is that the concepts of autonomy, affect, authority, authenticity, etc. are perhaps far more complex than the literature on Chinese learners has revealed. For example, while the profiles highlight the importance given to grammar and rules, they also highlight the importance of authentic learning in social contexts. While the profiles highlight the prevalence of authority and, to a degree, its acceptance, they also reveal a discontent and resistance to teacher-centered forms of learning.

The findings remind us that we still have much to learn about teaching and learning EFL in China. As Cortazzi and Jin (1996) argue, in spite of the fact that Chinese students make up approximately 25% of the world's learners, "as yet there is very little data-based research into their culture of learning" (p. 172). Other case studies such as the ones presented in this paper could be conducted to gain further insight into the same tensions and conflicts evidenced in our study. More interestingly and importantly, advancements in technology and the increased opportunities for Chinese learners to be exposed to western influences through media, the Internet and travel, may influence both experiences and beliefs related to EFL teaching and learning in China. Future studies might for example, inquire into the role that present-day access to computer and internet resources can play in improving EFL learning and teaching in China by providing access to authentic content and speakers.

Allen, L. (2002). Teachers' pedagogical beliefs and the standards for foreign language learning. Foreign Language Annals, 35(5), 518-529.

Armaline, W. & Hoover, R. (1989). Field experience as a vehicle for transformation: ideology, education, and reflective practice. Journal of Teacher Education, 40(2), 42-48.

Bailey, K. M., Bergthold, B., Braunstein, B., Fleischman, N. J., Holbook, M. P., Tuman, J., Waissbluth, X., et al. (1996). The language teacher's autobiography: examining 'the apprenticeship of observation.' In D. Freeman & J. C. Richards (eds.). Teacher Learning in Language Teaching (pp. 11-29). Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Bailey, K. M., Curtis, A. & Nunan, D. (2001). Pursuing professional development: the self as source. Boston: Heinle & Heinle.

Bond, M. (1996). The Handbook of Chinese Psychology. Hong Kong: Oxford University Press).

Borg, M. (2001). Teachers' beliefs. ELT Journal, 55(2), 186-188.

Borg, S. (1998). Teachers' pedagogical systems and grammar teaching: a qualitative study. TESOL Quarterly, 32(1), 9-38.

Brown, J. & McGannon, J. (1998). What do I know about language learning? The story of the beginning teacher. Proceedings of the 1998 ALAA (Australian linguistics association of Australia) Congress. Retrieved November 17, 2004 from http://www.cltr.uq.edu.au/alaa/proceed/bro-mcgan.html

Carter, B. (1999). Begin with beliefs: exploring the relationship between beliefs and learner autonomy among advanced students. U.S.: Texas papers in foreign language education. (ERIC Document Reproduction Service No. ED467863). Retrieved November 17, 2004 from E-Subscribe database.

Cortazzi, M. and Jin, L. (1996). Cultures of learning: language classrooms in China. In H. Coleman (ed.). Society and the Language Classroom (pp. 169-206). Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Cotterall, S. (1995). Readiness for autonomy: investigating learner beliefs. System, 23(2), 195-205.

Cotterall, S. (1999). Key variables in language learning: what do learners believe about them? System, 27(4), 493-513.

Creswell, J. W. (2005). Educational research: planning, conducting, and evaluating quantitative and qualitative research (2nd ed.). NJ: Pearson.

Gaskell, G. (2000). Individual and group interviewing. In M. W. Bauer & G. Gaskell (eds.). Qualitative Researching with Text, Image and Sound: A Practical Handbook (pp. 38-56). London: Sage publications.

Ho, J. and Crookall, D. (1995). Breaking with Chinese cultural traditions: learner autonomy in English language teaching. System, 23(2), 235-243.

Horwitz, E. K. (1985). Using student beliefs about language learning and teaching in the foreign language methods course. Foreign Language Annals, 18(4), 333-340.

Horwitz, E. K. (1988). The beliefs about language learning of beginning university foreign language students. Modern Language Journal, 72(3), 283-294.

Horwitz, E.K. (1999). Cultural and situational influences on foreign learners' beliefs about language learning: a review of BALLI studies. System, 27(4), 557-576.

Jackson, W. (2002). Methods: doing social research (3rd ed.). Toronto: Person.

Johnson, K. E. (1992). The relationship between teachers' beliefs and practices during literacy instruction for non-native speakers of English. Journal of Reading Behavior, 24, 83-108.

Johnson, K. E. (1994). The emerging beliefs and instructional practices of preservice English as a Second Language teachers. Teaching & Teacher Education, 10(4), 439-452.

Johnson, K. E. (1999). Understanding language teaching: Reasoning in action. Boston, MA: Heinle & Heinle.

Kagan, D. M. (1992). Implications of research on teacher belief. Educational Psychologist, 27(1), 65-90.

Kennedy, J. (1996). The role of teacher beliefs and attitudes in teacher behaviors. In G. T. Sachs, M. Brock, & R. Lo (eds.). Directions in Second Language Teacher Education (pp. 107-122). Hong Kong: City University of Hong Kong.

Kern, R.G. (1995). Students' and teachers' beliefs about language learning. Foreign Language Annals, 28(1), 71-92.

Kuntz, P. (1997). Students and their teachers of Arabic: beliefs about language learning. (ERIC Document Reproduction Service No. ED407854). Retrieved November 17, 2004 from E-Subscribe database.

Lee, I. (1998). Supporting greater autonomy in language learning. English Language Teaching Journal, 52(4), 282-289.

Mann, C. & Stewart, F. (2003). Internet interviewing. In J. F. Gubrium & J. A. Holstein (eds.). Postmodern Interviewing (pp. 81-108). London: Sage Publications.

Murphy, E. (2000). Strangers in a strange land: Teachers' beliefs about teaching and learning French as a second or foreign language in online learning environments. Doctoral dissertation. Québec: Université Laval.

Oxford, R. & Anderson, N. (1995). A cross-cultural view of learning styles. Language Teaching, 28(4), 201-215.

Peacock, M. (1999). Beliefs about language learning and their relationship to proficiency. International Journal of Applied Linguistics, 9(2), 247-265.

Peacock, M. (2001). Pre-service ESL teachers' beliefs about second language learning: a longitudinal study. System, 29(2), 177-195.

Raymond, A. M. (1997). Inconsistency between a beginning elementary school teacher's mathematics beliefs and teaching practice. Journal for Research in Mathematics Education, 28(5), 550-576.

Salili, F. (1996). Accepting personal responsibility for learning. In D. Watkins and J. Biggs (eds.). The Chinese Learner: Cultural, Psychological and Contextual Influences (pp. 85-105). Hong Kong: The Comparative Education Research Centre.

Strauss, A. & Corbin, J. (1998). Basics of qualitative research: techniques and procedures for developing grounded theory (2nd ed.). Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications.

Tillema, H. H. (1995). Integrating knowledge and beliefs: promoting the relevance of educational knowledge for student teachers. In R. Hoz & M. Silberstein (eds.). Partnerships of Schools and Institutions of Higher Education in Teacher Development. (pp. 9-24). Beer Sheva: Ben-Gurion University of the Negev Press.

Tsui, A. (1996). Reticence and anxiety in second language teaching. In K. Bailey and D. Nunan (eds.). Voices from the Language Classroom (pp. 145-167). Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Woods, D. (1996). Teacher cognition in language teaching: beliefs, decision-making and classroom practice. Cambridge: Cambridge university press.

Yin, R. K. (1993). Applications of case study research. London: SAGE Publications.

Zhang, L. J. (2000). Uncovering Chinese ESL students' reading anxiety in a study-abroad context. Asia Pacific Journal of Language in Education, 3(2), 31-56.

Zhang, L. J. (2001). Exploring variability in language anxiety: Two groups of PRC students learning ESL in Singapore. RELC Journal, 32(2), 73-91.

Zhang, L. J. (2003). Research into Chinese EFL learner strategies: Methods, findings and instructional issues. RELC Journal, 34(3), 284-322.

|

© Copyright rests with authors. Please cite TESL-EJ appropriately.

Editor's Note: The HTML version contains no page numbers. Please use the PDF version of this article for citations. |